The Most Notorious Rogue Employee Speaks

Cybersecurity lessons on the internal threat

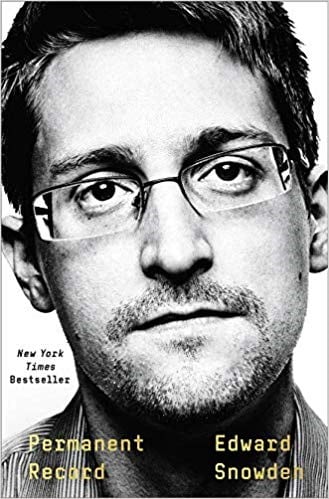

Edward Snowden, who has the distinction of stealing data from the most secure database in the world, has written a book. Called “Permanent Record,” it describes his exploits targeted on the NSA (National Security Agency).

For businesses there are two main lessons:

- The unfettered access that IT people have can take our companies down; and

- You may not be able to tell which employees you should be worried about.

Snowden’s prodigious technical skills were enough to allow him access to the entire cache of data – the “keys to the kingdom.” This same vulnerability exists every day at private companies!

And, Snowden underwent heavy background checks before obtaining the access, more background checking than the average company is able or willing to do.

There were no signs of potential disloyalty at the beginning. In fact, Snowden admits that when he first started in his intelligence community work he was a proud and dedicated member of his country’s defense forces. His attitude changed over time, though.

Snowden Describes the Access he Enjoyed

Their lack of technical knowledge gave Snowden’s superiors no choice but to trust him (in addition to the NSA he had interactions with the CIA):

“More than any other memory I have of my career, this route of mine past the CIA help desk has come to symbolize for me the cultural change…the moment when the old-school prepster clique that traditionally staffed the agencies, desperate to keep pace with technologies they could not be bothered to understand, welcomed a new wave of hackers into the institutional fold and let them develop, have complete access to, and wield complete power over …systems of state.”

The key terms: complete access and complete power. Without knowing the technology, employers cannot control, or even know, what IT staff are doing.

He goes on further, describing the consequences of this:

“Here is one thing the disorganized CIA did not understand at the time, and that no major employer outside of Silicon Valley understood either: the computer guy knows everything, or rather can know everything. The higher up this employee is, and the more systems-level privileges he has, the more access he has to virtually every byte of his employer’s digital existence. …and with the official title and privileges of a systems administrator, and technical prowess that enabled my clearance to be used to its maximum potential, I was able to satisfy my every informational deficiency…”.

This unfettered access is not unique to the intelligence community. It happens in virtually every company. This is generally, at least vaguely, known, but generally also accepted by management. Rather than acceptance, it has to be managed by access control, segmentation of duties, IT department monitoring.

So, We Need Honest Dedicated Employees – but How Do You Judge?

Snowden started out in the intelligence community as a proud hard-working asset to his agency and his country. He had passed the toughest security clearances. What happened? He saw things, and or felt things, that gradually made him change his attitude; one night, he says, “some dim suspicion stirred in my mind.” He was very young, only in his early twenties, and he says:

“There’s always a danger in letting even the most qualified person rise too far too fast, before they’ve had time to get cynical and abandon their idealism. I occupied one of the most unexpectedly omniscient positions in the Intelligence Community – toward the bottom rung of the managerial ladder, but high atop heaven in terms of access. And while this gave me the phenomenal, and frankly undeserved, ability to observe the IC in its full grimness, it also left me more curious than ever about the one fact I was still finding elusive: the absolute limit of who the agency could turn its gaze against. …”

Whatever we do in our companies most of us think it’s noble. An energy company thinks it’s keeping the lights on and heating our homes, but the not-yet-cynical young employee thinks it’s a corrupt polluter.

Snowden was young and had not yet had “time to get cynical.” In other words, he hadn’t gotten hardened prior to coming to the NSA and come to accept that the world might have injustices and/or might not always operate the way he would like. To the contrary, he became cynical while on the job – the worst-case scenario for his employer.

Becoming Cynical on the Job

When he started:

“I’m going to press pause here, for a moment, to explain something about my politics at age twenty-two: I didn’t have any.”

A few years later:

“Contradictory thoughts rained down like Tetris blocks, and I struggled to sort them out – to make them disappear. I thought, pity these poor, sweet, innocent people – they’re victims, watched by the government, watched by the very screens they worship. Then I thought: shut up, stop being so dramatic – they’re happy, they don’t care, and you don’t have to either. Grow up, do your work, pay your bills. That’s life.”

Eventually, at age 29:

“… organizations like the NSA – in which malfeasance has become so structural as to be a matter not of any particular initiative, but of an ideology….they’d hacked the Constitution.”

It’s hard to know for sure who might become that rogue employee, but awareness by management can help. Snowden’s attitude evolved over years and would have been spotted if anyone had been looking.

Some Preventive Ideas

The IT department is where access and control lie. We’ve discussed it is impossible to know for sure who we can trust. So someone outside of IT has to be watching what IT is doing. Whether this is a separate internal audit team or an independent contractor, oversight is necessary. Often these oversight units will report to the CFO. Please see CFO take charge of infosec for some build-out of this thought process.

Re Cyber Insurance coverage, we need to understand the coverage for loss from rogue employees. Insurers like to take the position, in an increasingly forceful way, that the policy will not cover actions by members of the “control group.” If the definition of control group is limited – say to CEO, CFO and General Counsel – we might have to accept that, lacking better options. Perhaps the insurer has a right to say that they would be insuring the owners or managers of the company for their own actions!

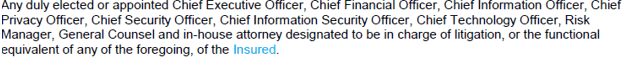

But, the definition of “control group” whose members’ actions would be excluded in the Cyber policy, is continually expanding over time. We just now reviewed a Cyber policy where the excluded actions included those of all these persons:

There is no way to control or know the intentions of all the persons listed above (including their “functional ‘equivalents’ ” as well!). The persons whose actions are excluded need to be limited to a very small, very top-level, list.

The rogue employee phenomenon is not common, and this is a blessing and a curse. Why it’s a blessing is obvious, but why it’s a curse may not be. The problem with rare, potentially very severe, events is that their remoteness can cause us to ignore them. We focus on frequent events because they are always in front of us. If we do forget about the rare one, that can be the one that takes the company down. Risk managers are always forcing attention to the severe event – the frequent one automatically gets all the attention it needs.

(c ) Licata Risk & Insurance Advisors, Inc. 2019

Frank Licata

[email protected]; 617.718.5901

Dec 16, 2019